Gauging the overall success of a public relations campaign is simple enough in hindsight, but recognizing the moment when it reaches a tipping point and the weight of public opinion shifts and congeals around a particular point of view is much harder. Managing a PR issue is usually a drawn out process, and it’s often difficult to know when a change in public opinion is occurring. Even when it’s all over, the post-mortem analysis is messy and inconclusive; participants often have different views on what won the fight or lost it.

The problem of measuring PR results is an old one. Chief executive officers, accustomed to looking at sales figures and revenue growth, are known to question the value of PR when they sign off on the budget, even while in the middle of a big public fight. They would rather pay attorneys because they guarantee a definitive event, whether through winning, losing or settling the case.

On the other hand, ask ten good PR executives how an issue might play out and you’re likely to get 20 (or more) different answers. Unless your agency has the resources to poll like a political campaign, it’s difficult to measure shifts in public perception over a short period of time. It takes time for news reports to crystallize and for ideas to become consistently held opinions.

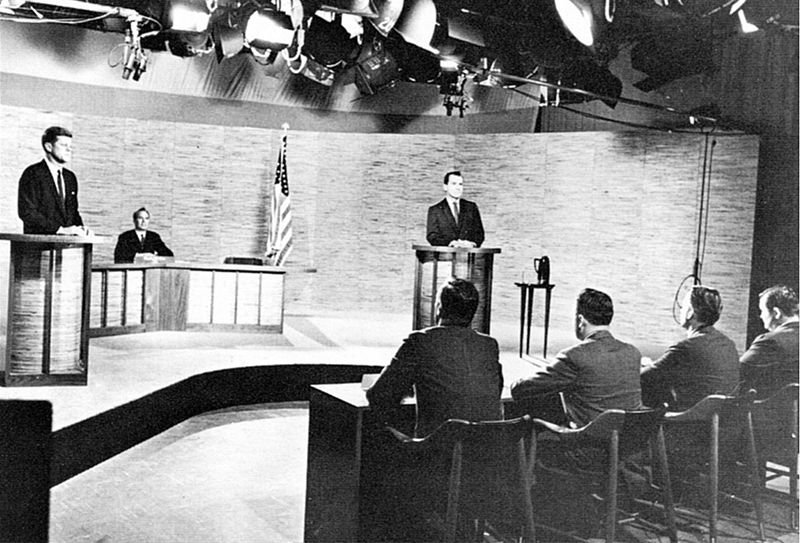

The presidential election is the ultimate public relations campaign, but it provides the unique benefit of a reckoning at the end. On November 7, 2012, we will know who will reside at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue for the next four years. For that reason, it may be the ultimate laboratory for understanding how public perceptions change. I grant you that everything is exaggerated in a political campaign – it plays out over a much shorter period of time – but that is how laboratories work. In hyperbole, we may find some modicum of truth.

The 2012 election is in full swing, so now is a good time for skeptical business executives to tune in if they want to understand how good or bad PR moves impact public perception. In all the chaos of political ads, speeches, bus tours and press conferences, there will be a moment or two that historians will point to years from now as critical junctures.

First, watch the polls. President Obama and Mitt Romney are currently neck-and-neck, but when those numbers begin to change, pay attention to the pundits and their analysis. It’s possible one event could change the race, and it may be something that neither campaign is anticipating. Consider 2008 when the economy tanked and McCain temporarily suspended his campaign. Most politicos argue that was the moment he began to lose.

Takeaway: External events you cannot control are a threat. Determine now what you can do to minimize their potential impact.

Second, did one candidate win the race or did the other lose it? In 2004, John Kerry went wind surfing, but George Bush sailed on to victory. While there were certainly other factors – including Bush’s general likability – the photo of Kerry windsurfing off Nantucket proved to be an iconic image from the campaign. The snapshot perfectly illustrated Kerry’s inability to connect with voters, driving home the argument his opponents had made for months.

Takeaway: Are you losing to a better opponent or beating yourself? When managing a PR crisis, the smallest details matter. An off-the-cuff remark can change public opinion overnight (think: “I just want my life back”).

Third, pay attention to the daily campaign volleys as accusations are dispatched and answered by the candidates. An over-eager defense can be viewed as a sign of desperation. For example, Romney lined up interviews with every major network news station after the Obama campaign launched a blistering attack on his tenure at Bain Capital. Some called it desperate.

Takeaway: Forceful when faced with an attack is good, but overreaction signals fear. Consider the tone and setting of your response. Flashy press conferences or angry interviews can overpower otherwise effective messaging.

The fact that public relations campaigns are complicated and results are difficult to measure does not mean they cannot be won through sound strategy and effective execution. Presidential campaigns prove that the public has a long memory and public relations missteps, strung together, eventually come to define a candidate.

Company reputations aren’t much different. It may be hard to point to a moment when everything changes, but there is usually a defining mistake that illustrates a deep suspicion the public was already beginning to believe. That’s the turning point. If you’re lucky, you’ll get to see one in the next two months.

Image Credit: National Park Service, Images of American Political History

As design director at Cookerly, Tim serves as the creative lead in the development of branding campaigns, print collateral and digital media for clients across a broad range of industries, including consumer, professional services, healthcare and technology.

As design director at Cookerly, Tim serves as the creative lead in the development of branding campaigns, print collateral and digital media for clients across a broad range of industries, including consumer, professional services, healthcare and technology. As senior vice president at Cookerly, Mike Rieman specializes in building and maintaining relationships with the media and has an excellent track record of landing significant placements in print and broadcast media including USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Money Magazine.

As senior vice president at Cookerly, Mike Rieman specializes in building and maintaining relationships with the media and has an excellent track record of landing significant placements in print and broadcast media including USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Money Magazine.

As vice president of Cookerly, Sheryl Sellaway uses her extensive corporate communications background to lead consumer PR efforts, deliver strategy for marketing programs and share expertise about community initiatives.

As vice president of Cookerly, Sheryl Sellaway uses her extensive corporate communications background to lead consumer PR efforts, deliver strategy for marketing programs and share expertise about community initiatives.

As a senior vice president at Cookerly, Matt helps organizations protect and advance their reputations and bottom lines through strategic communications programs. Using creativity, planning and flawless execution, he works with a team to deliver compelling public relations campaigns that produce results and support clients’ business objectives.

As a senior vice president at Cookerly, Matt helps organizations protect and advance their reputations and bottom lines through strategic communications programs. Using creativity, planning and flawless execution, he works with a team to deliver compelling public relations campaigns that produce results and support clients’ business objectives.

No Comments